Class Politics and Fashion: Menswear Week

Jeremy Allen White, Ralph Lauren and I know I'm avoiding politics

First, before I go more deeply into the recent menswear commentary, I just want to say that I know I’m avoiding the politics of the moment. I’m sick to my stomach about the neverending wars, I’m sick of the primaries and and the two party system. I’m sick of China Watch, I’m sick of all the pundits. By the way, Donald Trump is the clown version of the primal father, who lies before civilization begins, who needs to obey all laws. My question is why does American civilization suck so much that we want him to destroy it for us? Freud called this hostility to civilization discontentment and it lay at the heart of Fascism, or the worship of violence.

So yes, I’m escaping into a discussion of menswear this week. Richard Armstrong in the Financial Times concludes his article on American style with the following sentences, “Even as we become a nation of service workers and data manipulators, workwear is everywhere. Class consciousness is inscribed in our clothes.”

OK, that sentence is actually just wrong. Class consciousness is repressed in our clothes might be better formulation: Armstrong points to how American menswear is torn between Brooks Brothers and Carhartt, with Ralph Lauren, from a working class background representing our ambivalence about both.

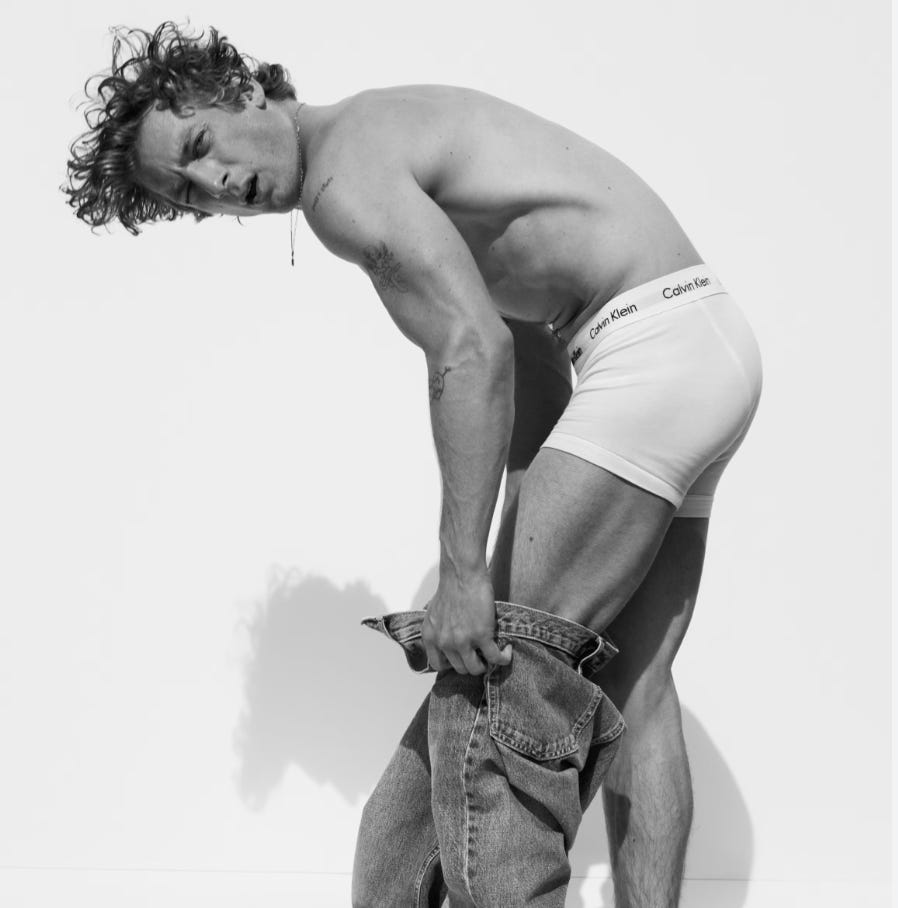

Then there was commentary about the Calvin Klein video featuring Jeremy Allen White that allegedly broke the Internet.

The New York Times published this piece by cultural commentator Soraya Roberts titled in full, “The Lascivious, Decades Long History Behind that Calvin Klein Ad: Jeremy Allen White Joins the Pantheon of Underwear Gods Balancing Heroics with Sleaze.”

Unlike the Financial Times, that actually possesses some class consciousness, The New York Times publishes a slightly shaming piece about “the history” of one of the sexiest Calvin Klein underwear ads ever made — with the words lascivious and sleazy in the title.

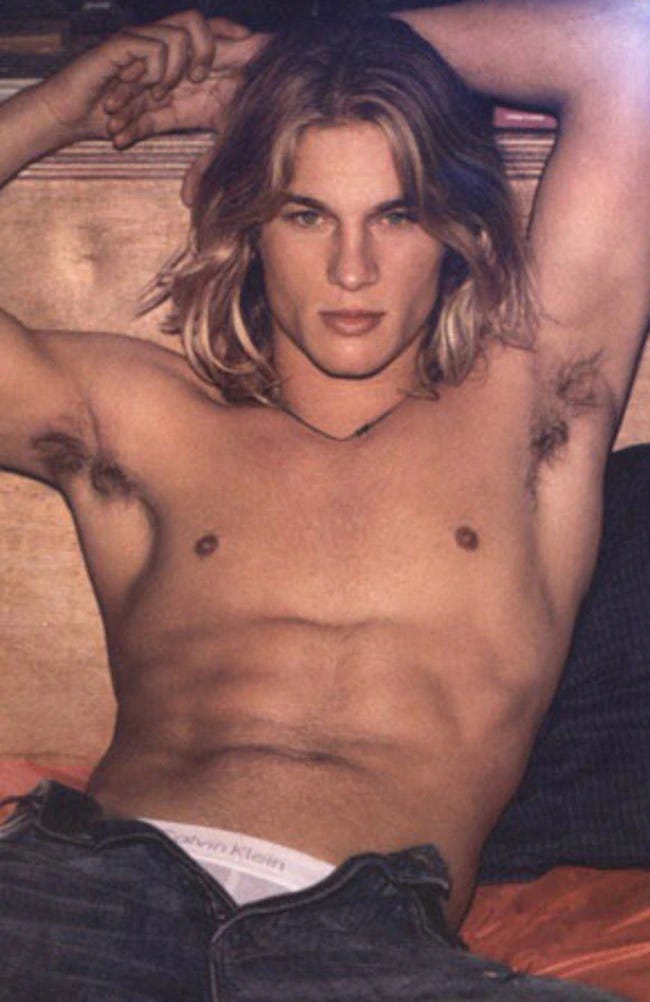

Roberts talks about Mark Wahlberg and Travis Fimmel,

who were successful underwear models for the fashion company and then goes on to wonder with Jacob Elordi’s ads never had the same impact as Wahlberg’s, Fimmel’s or Jeremy Allen White’s.

I’ll give Roberts a clue: it has to do with the sexuality of the working class aura around those three models that make them truly sexy. Elordi was well cast in Saltburn as a feckless scion of an unimaginably wealth and aristocratic family.

Wahlberg was of Queens, Fimmel looked like he needed to take summer jobs as a gigolo to get through his last year of high school and Jeremy Allen White as Carmy was all bicep and white T-shirt. I wrote about service economy heroics here in Damage and here on the Substack.

There was a time when the strength of men and their ability to perform physical labor was important to capitalism.

The hard work of the fields, factory and mines did produce beautiful men and beautiful bodies that the rich and gouty might admire from afar. Think about Irish boxers and African American athletes. But the Greco-Roman aesthetic of the male body was a product of leisure and now expensive trainers and gym memberships.

Soraya Roberts makes embarassed mention of Leni Riefenstahl and her cinematography of heroic male bodies for Hitler’s Olympics. It is undeniable that at least one shot of Allen White’s body, camera low, Allen White’s body unfurled like a muscle flag against the sky owes very much to the Nazi director, but Roberts shies away from drawing conclusions about Fashy Fashion.

In Diego Rivera’s murals, the bodies of the working class men were flexed at work, not at play: their power was supposed to manifest working class power and anguish.

The bodies of the working class were consumed quickly by physical labor under industrial capitalism. Today working class bodies are being destroyed by Big Food, Big Ag and the foodways of a country that is willing to sell its guts to some of the biggest and most evil corporations in the world.

Roberts calls the whiff of working class male charisma “sleaze” : of course it is off limits except as pure object to readers of the New York Times, especially its heterosexual female readers, Professional Class aspirants who must make the best match with its post-industrial worker, a well paid data manipulator.